Disclaimer

Value Situations is NOT investment advice and the author is not an investment advisor.

All content on this website and in the newsletter, and all other communication and correspondence from its author, is for informational and educational purposes only and should not in any circumstances, whether express or implied, be considered to be advice of an investment, legal or any other nature. Please carry out your own research and due diligence.

Food may not be the answer to world peace, but it’s a start.

Anthony Bourdain.

The energy crisis that began last year was one of the main economic and financial market stories of 2021, and it’s a theme that is set to continue this year - as I write this, WTI crude oil (CL1) is up ~10% and natural gas (NG1) is up ~26% YTD, with expectations that energy prices will remain high into 2022.

Looking at the performance of the Q&G complex over the last 12 months, I can’t help but feel that I missed out on a unique and contrarian value situation - looking back to the beginning of last year one could have discerned something was brewing here. The lack of investment in the O&G sector, reduced fuel stockpiles and the potential for a supply crunch were well known factors as we entered 2021. This set-up combined with the knowledge that a vaccine roll-out programme would most probably pull the global economy out of the COVID-induced recession of 2020 clearly suggested energy stocks were an area of opportunity. If nothing else, the energy sector weighting within the S&P 500 index in early 2021 (at an all-time low of ~2%) surely pointed to a possible inflection point:

Source: Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates, LLC

And so it was, as O&G stocks appreciated substantially and outperformed in 2021.

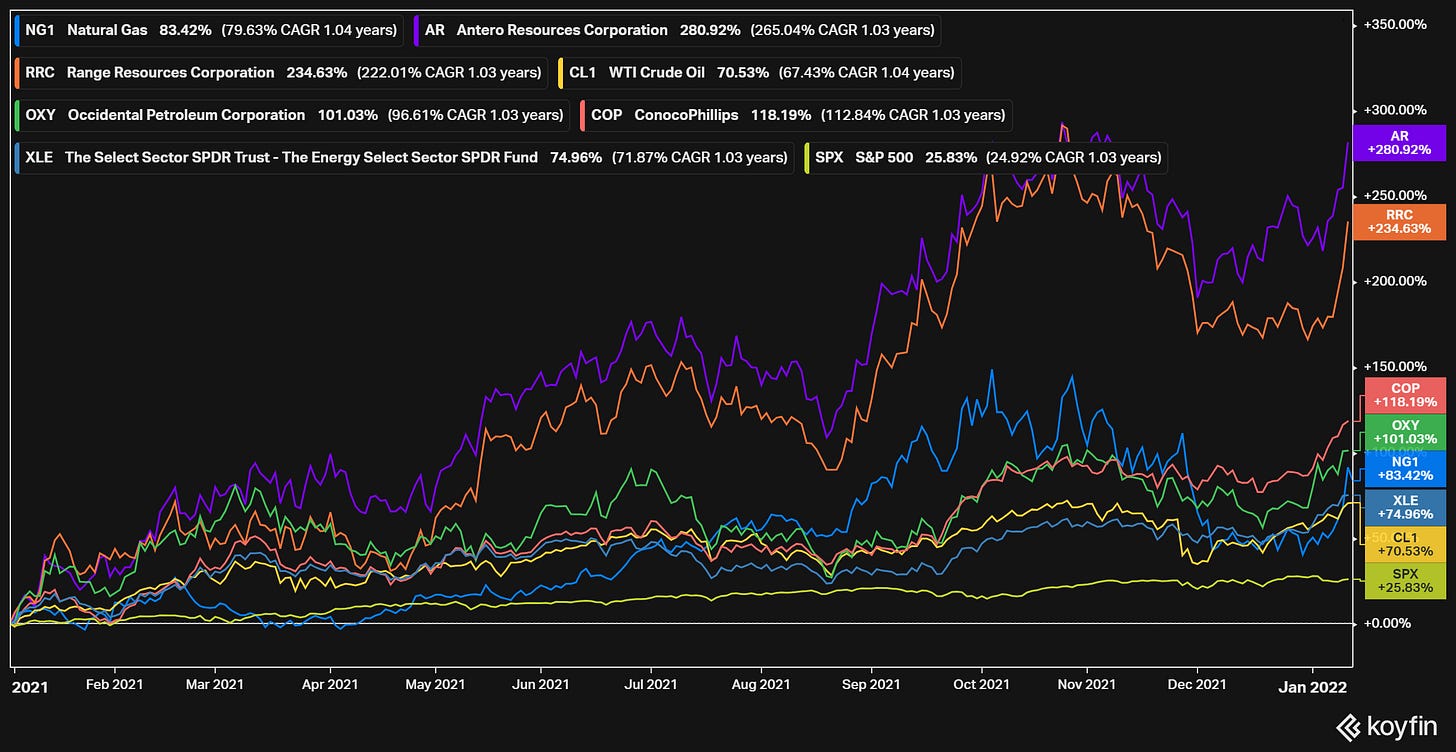

So what was the extent of the opportunity? Looking at the actual commodities themselves, oil (CL1) has risen by ~70% to date since 31 December 2020, while the price of US natural gas (NG1) has increased by ~83% over the same period:

Not surprisingly, while XLE (the US energy ETF) tracked the commodities performance, rising by ~75% to date, individual O&G companies offered much greater torque on the theme and selected O&G names substantially outperformed, from Occidental Petroleum rising ~101% to Sandridge Energy rising by ~290% to date as shown in the chart above.

That’s some serious out-performance by O&G vs some of the headline benchmarks and popular names:

S&P 500, + ~25% to date since beginning of 2021 (as at time of writing)

Tesla, + ~57%

Apple, + ~33%

XLK (US large cap tech ETF), + ~31%

ARKK, the formerly celebrated tech-innovation ETF, down - ~32%

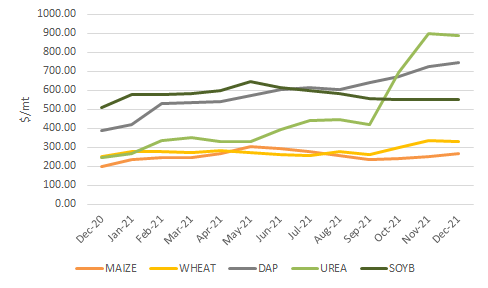

But coming back to energy commodities and specifically natural gas, one of the most significant effects of the surge in natural gas prices has been its impact on fertiliser prices. Natural gas is the main feedstock used in the production of nitrogen fertilisers, namely ammonia and urea, and accounts for 60%-80% of the production cost of these. The spike in natural gas prices led to a corresponding spike in the price of fertiliser at the onset of last year’s autumn/winter crop planting season:

Source: World Bank.

The price of diammonium phosphate (DAP) and urea fertilisers increased by 92% and 263% respectively in 2021, compared with a 47% increase in US natural gas prices and a 549% increase in European gas prices. (The reason for the spread between US and European gas prices has to do with source of supply - the US controls virtually all of its own gas supply, while Europe depends on its politically sensitive relationship with Russia for much of its gas supply - ~40% of the EU’s gas comes from Russia. Indeed the perilous state of the European energy market and policy has been well reported on).

Similar to the O&G complex, fertiliser equities performed strongly over the past ~12 months, powered by the underlying surge in fertiliser prices:

Of course hindsight is 20-20, and it’s easy to say now that I’ve missed out on an asymmetric value opportunity in natural gas and fertiliser as a second-order play on the energy theme. It’s possible that the theme will play out further but I don’t think gas and fertiliser stocks can offer the same degree of asymmetric upside from current levels. But this does prompt the question of whether there is another way to play the ongoing energy crisis (and the wider inflationary outlook) among assets that have not yet participated in price increases to the same extent as energy commodities and fertiliser.

Having read the Doomberg team’s excellent Starvation Diet piece last year (I’d highly recommend people read and follow Doomberg) and amid increasingly urgent headlines about food inflation and shortages, I believe food and agricultural commodities, and specifically staple crops are the next phase of the energy/natural gas/fertiliser dislocation. By staple crops here I’m referring to soybeans, corn and wheat which are essential to the global food supply. Why these crops in particular? Fertiliser is required to grow these crops at a scale sufficient to feed populations. Furthermore, corn and soybeans are the main feed grains used in the production of animal feed for cattle, pigs, sheep etc, while wheat is the main ingredient for bread. So it should be very obvious how the rise natural gas prices will inevitably ripple (or whip) through the global food supply chain.

However, given the interconnectedness of the natural gas-fertiliser-crop chain, it is somewhat curious that crop prices have not risen to the same extent as fertiliser prices over the last 12 months. As noted above and again charted below, while DAP and urea prices surged in 2021, crop prices did not rise nearly as much - in 2021 soybean prices rose by just 8%, corn (maize) by 33% and wheat by 31%::

Source: World Bank.

Looking back through the previous cycle, the last time fertiliser (DAP and urea) prices spiked to the same extent as 2021 was in 2008, which was one of the main drivers of the 2007-2008 world food crisis:

Source: World Bank.

During the 2008 food crisis, soybeans, corn and wheat rose by 108%, 74% and 138% to their respective peaks around Q3 2008 - while these crops are approaching 2008 prices in absolute terms they have not risen by anywhere near the same in % magnitude terms over the last 12 months, despite the spike in the fertilisers essential to their production:

Source: World Bank.

Of course, the price of gas and fertiliser alone does not determine crop prices and it’s important to state that agricultural commodity markets are extremely complex, being influenced by some very dynamic variables, which incidentally all point to food supply interruption and inflation:

Political and trade issues - this includes a broad range of unpredictable issues and risks, much of which relates to geopolitical tensions between Western democracies and Russia and China currently. Included within this category are:

Energy security and shortages (e.g. Russian gas supply into Europe).

Resource nationalism (e.g. Russian agricultural policy, Chinese stockpiling of commodities, including crops).

Export restrictions, including Russian export taxes on wheat, Chinese and Russian restrictions on fertiliser exports (both countries are major producers of fertilisers) until the end of June 2022, which notably reduces available supply of fertiliser inputs for other countries during this spring’s planting season. China and Russia have implemented these restrictions to ensure there is enough fertiliser for domestic food production, thus mitigating the risk of civil unrest from resultant food shortages.

Belarussian potash trade sanctions - Belarus is one of the largest producers of potash, another major type of fertiliser used to produce crops.

The recent political and civil unrest in Kazakhstan, initially triggered by fuel price inflation, also raises the prospect of further food inflation and price volatility, with Kazakhstan being a major producer and exporter of wheat and wheat flour.

These factors all directly impact current global food production and supply chains, thereby increasing the risk of food shortages and inflation.

Weather - agriculture is one of the most exposed sectors to climate change, and as increasingly erratic and adverse weather events become more frequent due to climate change (which circuitously, natural gas and fertiliser production is seen as a major contributor to), food supply will become increasingly disrupted, thereby increasing food insecurity and driving prices higher. Recent events that have damaged crops and contributed to food price increases include the La Niña weather pattern, which has previously caused droughts, flooding and frosts that have damaged crops. Notably, weather forecasters are predicting another La Nina weather event in 2022.

Supply and Demand - obviously fundamental supply and demand underpins market prices for crops, but the S&D mechanism is especially complicated for agricultural commodities given the unpredictable (and unhedgeable) political and weather risks noted above, in tandem with energy prices. The demand side is most obviously driven by population growth and economic activity, but again this has become more complicated in recent times by national food stockpiling initiatives, most obviously in China for geopolitical reasons, but also more broadly in other countries as part of a switch to a “just-in-case” supply chain model in response to COVID disruption.

Biofuels - more recently soaring demand for crops as inputs in the production of biofuels such as renewable diesel has contributed to higher food prices (another unintended consequence of ESG investment and policy responses to global warming). Staple crops such as soybeans and corn are among the main feedstocks for biofuels, meaning growth of these crops is increasingly being diverted out of the food supply chain into biofuel production. With biofuels seen as part of the energy transition, major oil refiners including ExxonMobil, Chevron and Marathon have increased investment in renewable fuel production, indicating a new structural source of competing demand for farm acreage and crops which will reduce the available supply of crops for food production.

Supply Chain Disruption - supply chain disruption is a well understood and ongoing product of the COVID pandemic, but it has a particularly severe impact on food supply and therefore food inflation. All aspects of the supply chain have been impacted by the pandemic, from surging freight costs to rising fuel costs to labour shortages. With freight and fuel costs expected to continue to rise in 2022, food prices are likely to remain elevated also.

The supply chain point with respect to oil prices also leads to an interesting observation that no one seems to be discussing in the context of current energy and food price inflation. While natural gas is the key commodity that underpins the growth of crops via fertilisers, it actually has a much lower correlation to food prices than oil:

Source: World Bank data; Value Situations analysis.

Based on data from 2007-2021 (which includes two previous food crises in 2007-08 and 2011-12), US natural gas prices have exhibited a correlation co-efficient of 0.22 with soybeans, 0.14 with corn and 0.28 with wheat, which statistically speaking suggests a weak positive relationship. Contrast this with oil, which has a much stronger correlation to crop prices:

Source: World Bank data; Value Situations analysis.

Over the same period, oil exhibited a correlation co-efficient of 0.70 with soybeans, 0.66 with corn and 0.63 with wheat, i.e. oil has a statistically strong positive correlation to these crops:

Source: World Bank data; Value Situations analysis.

Oil’s positive correlation with crop prices makes sense, given that oil is a critical input to agricultural production, both directly (via fuel to power equipment, machinery and transport) and indirectly (via pesticides and chemicals used in growing and production). Given the robust, inflationary outlook for oil this year and beyond, with the prospect of $150/barrel or even $200/barrel prices seen as plausible in the coming years, this further indicates the strong prospect of sustained food price inflation. In simple terms, an inflationary outlook for oil is an inflationary indicator for crops and food prices.

Yet when we look at futures prices for soybeans, corn and wheat the market is not pricing in any significant price increases for these crops - in fact the market is pricing in steady declines in crop prices out to 2024-25:

CBOT Soybean Futures Prices

CBOT Corn Futures Prices

CBOT Wheat Futures Prices

Source: CBOT; Barchart.com

A gradual decline in crop prices seems incongruent with the wider macro-economic backdrop of a growing global population, elevated energy and fertiliser prices, increased geopolitical uncertainty, resource nationalism/stockpiling, ongoing supply chain disruption, and increasingly volatile weather systems.

If one steps back at looks at the confluence of these macro-factors occurring now, it suggests a perfect storm for food prices in the years ahead. My view is these factors will likely drive structurally higher food prices and most likely another food crisis in the coming years. I therefore believe food prices, and specifically key crops such as soybeans, corn and wheat are the likely next phase of the current energy crisis. In this light, I expect the agricultural commodity complex to benefit from this situation in 2022-23, similar to how natural gas and fertiliser producers performed in 2021.

So how might this play out?

The surging price of fertilisers during the 2021 winter planting season reduced the affordability of fertiliser for farmers, meaning lower fertiliser application for crop growth. This implies that both the quality and quantum of crops to be harvested this coming spring will be lower as a result, and that’s before factoring in other potential supply shocks such as a Russian invasion of Ukraine, or adverse weather events. Notably, last Saturday’s volcano eruption and tsunami in Tonga could pose an unforeseen supply threat - a large amount of sulphur dioxide gas was released by the eruption, which could cause acid rain that would damage crops already planted. Tonga’s relative proximity to Australia and South America could mean wider crop damage should volanic ash travel to these regions (Australia, Brazil and Argentina are major crop producing nations). For an example of the potential wider impact, we only need to look at Peru which is approximately 10,000km to the east of Tonga, and has already seen towns flooded as a result of the tsunami triggered by the eruption.

Furthermore, the upcoming 2022 planting seasons in spring and winter would appear to be at risk given that energy and fertiliser prices remain elevated with the potential to rise further this year, and against the backdrop of continued supply chain issues, labour shortages and geopolitical risks. Despite recent declines in fertiliser prices, I’m not convinced these will last and I see a fertiliser supply crunch as a real possibility, and would highlight again that both China and Russia have restricted the export of fertilisers until June 2022, bypassing the spring planting season. In this light, I do not believe the futures markets are pricing in the risks here.

All of this points to a challenging situation for agricultural commodity production and therefore food supplies this year and into 2023. So how might one play this situation?

In the next issue issue of this newsletter, I will present a public equity situation that I believe offers a way to play this theme, and which the market has overlooked relative to natural gas and fertiliser equities.

"Food prices" where, and for whom? I tend to be frustrated when non-macro investors step in to make broad commodity calls because these systems are much more dynamic than any given cause-effect relationship. Many commodity prices — especially those most important to the average person — are driven in all kinds of crazy directions by government action, and they can stay that way indefinitely. With food prices in particular, I can't think of a single issue that's more instantly (and intensely) political. Why wouldn't world governments just step in to drive down prices? What levers would they use to do so if they felt they had to? How do these second- and third-order effects interact with the possibility of opportunities in this space?

The US once decided to prop up its local cotton growers with subsidies that negatively impacted competition in Brazil. The WTO declared those subsidies unlawful in 2004, the US appealed, and after years arguing in appeals, Brazil still prevailed. With appeals settling in the delicate aftermath of the GFC, rather than repeal the local subsidies, and unwilling to face retaliatory taxation from Brazil on US exports, the US decided it was easiest to just pay Brazilian cotton farmers $147 million/year. "Fuck it, write 'em a check."

The US is already seeing intense political pressure to "do something" about inflation, and of course more interventionist regimes like China's are already much more heavily involved with trying to manage commodity prices. What happens when this becomes something that gets broad fiscal firepower behind it?

In Diary Of A Very Bad Year, the anonymous hedge fund manager being interviewed remarks that his firm actively avoids taking a directional position on any of the major currency crosses because they tend to be mean reverting over time and they're ultimately driven by central banks and fiscal policy makers. He remembers going to an "idea pitch" dinner with other hedge fund managers, and everyone was very bullish on the euro, bearish on the dollar:

"Now, considering that everyone at the table being super-bearish on the dollar probably meant that they were already short the dollar and long the euro, I went back and basically looked at my portfolio and said: “Any position I have that’s euro-bullish and dollar-bearish, I’m going to reverse it, because if everybody already has said ‘I hate the dollar,’ they’ve already positioned for it, who’s left?” Who’s left to actually make this move happen? And who’s on the other side of that trade? On the other side of the trade is the official sector that has all sorts of other incentives, nonfinancial incentives, political incentives. They want to keep their currency weak to promote growth or exports or jobs. Or they have pegs, peg regimes, that they need to defend, and they don’t really care about maximizing profit on their reserves. They’re not a bank trying to maximize profits, they have broad policy objectives—and infinite firepower."

I wouldn't disagree that there's possible opportunity here, but I really want to hear the part where those opportunities are aligned with (and not facing off against) the counter-parties with infinite firepower and no profit incentive.

great stuff, as always