EV transition on ICE?

A mispriced equity play on a delayed transition to electric vehicles, offering 50% - 120%+ upside.

Disclaimer

Value Situations is NOT investment advice and the author is not an investment advisor.

All content on this website and in the newsletter, and all other communication and correspondence from its author, is for informational and educational purposes only and should not in any circumstances, whether express or implied, be considered to be advice of an investment, legal or any other nature. Please carry out your own research and due diligence.

The Climate Change Committee have rightly said you don’t reach net zero simply by wishing it…. So, to give us more time to prepare, I’m announcing today that we’re going to ease the transition to electric vehicles. You’ll still be able to buy petrol and diesel cars and vans until 2035. Even after that, you’ll still be able to buy and sell them second-hand.

Rishi Sunak, PM speech on Net Zero, 20 September 2023

The hardest question of all, and the dreariest to contemplate, is whether the green transition will happen at all. The proliferation of electric cars and renewable energy may stall for lack of human will, and the associated copper demand may never show up. It is an ugly possibility to contemplate, but it has to take up significant space in any copper investor’s probability distribution.

Copper as lifeline and as investment, Financial Times, 15 September 2023.

There’s no way we can supply the amount of copper in the next 10 years to drive the energy transition and carbon zero. It’s not going to happen.

Doug Kirwan, Copper Mine Flashes Warning of ‘Huge Crisis’ for World Supply, Bloomberg, 3 May 2023.

The opening quote from UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s recent “u-turn” speech on net zero targets signaled a dramatic climate policy shift, delaying a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars within the UK by 5 years (to 2035), bringing the UK in line with the EU, Australia, and several US states for the phase-out of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles.

Interestingly, in the days following Sunak’s announcement EU ministers voted to water-down the European Commission’s Euro 7 proposal on vehicle emissions, essentially to protect certain European auto manufacturers’ competitiveness. While this vote means no change to the EU’s existing testing conditions and emissions limits for cars and vans, it does provide scope for furthering tightening of emissions controls in subsequent years.

These latest developments in the UK and Europe also follow Japan’s divergent approach to achieving net zero targets via a proposed slower pace of transition, given its relatively different circumstances compared with other countries in term of its grid infrastructure and energy security concerns.

I believe these latest policy events signal a growing realisation that despite all the idealistic targets, platitudes and activism, the energy transition is not a forgone conclusion; as Sunak succinctly put it “you don’t reach net zero simply by wishing it.”

And so these latest headlines have prompted me to consider again a question I’ve been mulling over for some time, and which the FT recently touched on, as referenced in the second opening quote above; what if the energy transition doesn’t actually happen? Or at least is significantly delayed? After all, since 2004 a cumulative total of $6.7 trillion has been invested in the energy transition globally, yet in that time fossil fuels’ share of primary energy has fallen by just ~4.5%, to 81.8% in 2022 from ~86.3% in 2004. Furthermore, despite this investment an unprecedented amount of further investment (likely in the $ trillions) is required if the energy transition is to be achieved, which involves overcoming all sorts of hurdles that currently seem very ambitious and even unrealistic.

Copper is one such hurdle that has been well reported on, and is emblematic of the broader challenge of delivering on the energy transition. Robert Friedland, the mining financier and founder of Ivanhoe Mines, has long highlighted the enormity of the challenge involved in seeking to achieve net zero targets with regard to the mining of copper and other critical minerals. According to Friedland, all the copper that has ever been mined in the history of humanity amounts to ~700m metric tonnes; however humanity needs to mine the same amount again in the next 22 years just to maintain a 3% GDP growth rate, and that is without the process of electrifying the world economy (!):

Source: Robert Friedland, presentation at Investing in African Mining Indaba 2022.

Given the broad global consensus on the need to decarbonise the world economy and achieve net zero targets, this implies truly enormous future demand for copper on a scale that makes one wonder whether it is even achievable. Energy education and information group EnergyMinute estimates that the world needs ~1.4 billion tonnes of new copper supply by 2050 to achieve net zero targets - to put that in perspective that equates to ~2x all the copper mined over the past ~3,000 years!:

Source: EnergyMinute.

The reason for such an enormous future requirement lies in the fact that electrification, from EVs to wind turbines, to solar panels, to upgrading the electrical grid, is extremely metals intensive, requiring vast amounts of copper (as well as other transition metals such as cobalt, graphite, manganese and nickel for EV batteries).

As Friedland explains:

"We can't get there without electrifying the world economy. It's the electrify everything era, but the problem is that renewable technology is absurdly metals intensive… wind and solar energy is between seven and 37 times more copper intensive than conventional electricity and the global wind turbine fleet is to consume more than 5,5MT of copper by 2028… the mining world now faces a huge challenge!”

In addition, Friedland has also highlighted how power grids globally are unreliable, with huge investment needed to upgrade them:

"Electricity grids are old and cannot handle all electrification of the world. How much copper will we need to build new smart grids in Europe, US, and what about Africa?"

Against this surging demand backdrop a global copper shortage is looming due to several factors, including:

Under-investment during the previous cycle, with very little investment in new mines;

Depletion of existing mines, with lower grade copper being produced (making production more costly and less efficient), with fewer high grade copper mines remaining;

Long lead times for new mines exacerbating supply constraints, including onerous permitting requirements - on average it takes ~15.7 years for a new copper mine to come online, from discovery to production, further choking new supply and exacerbating supply/demand imbalances;

Financing new mines is difficult due to both the inherent risk profile involved in mining (operational, jurisdictional, commodity price volatility), and more recently due to ESG considerations - mining is a “dirty” activity and as such is not an ESG-compliant use of capital, resulting in limited capital available to fund new supply. (Also with base interest rates rising over the past ~18 months, the hurdle rate for new projects has also risen, further limiting capital availability).

Obstructive regulatory backdrop, with general opposition to mining activities due to ESG-driven environmental concerns. This has led to the absurd situation today where policymakers globally are pushing for a decarbonised economy while at the same time opposing the mining activity required to actually extract the minerals essential to achieving decarbonisation (note this is further compounded by opposition to fossil fuels and energy market disruption, given that the mining industry relies primarily on coal, oil and natural gas to power operations, equipment and vehicles - alternative fuel and power sources are still a long way off the scale and efficiency required to replace the industry’s fossil fuel usage);

Labour/Skills Shortage, with mining companies struggling to find enough skilled workers such as engineers, exploration geologists and data analysts to support operations and grow production; simply put, there aren’t enough qualified people available currently or in the education pipeline to do the work necessary to help implement the energy transition.

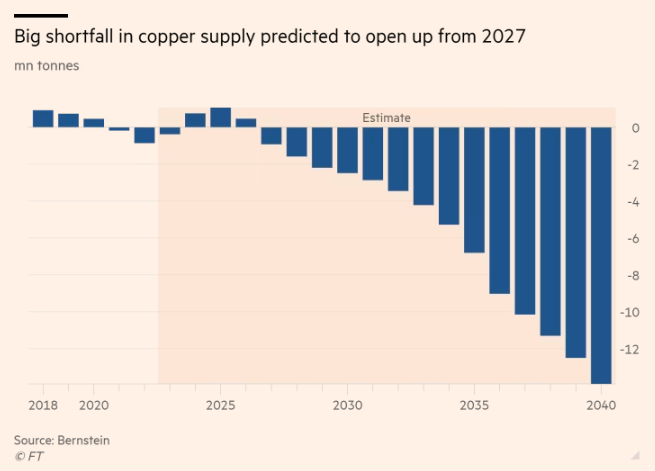

These factors have been known for some time, and industry executives have consistently warned of a supply shortage and even a supply “train wreck” threatening the energy transition, with a significant supply shortfall now expected by 2027 onwards:

Source: Bernstein / FT.

Given this supply/demand set-up, last month at the FT Mining Summit, Kathleen Quirk, President of Freeport-McMoran (FCX) stated that “What may end up happening is that this [energy transition] gets extended out longer.”

Additionally, its worth emphasising that the constraints and obstacles outlined above relating to copper also apply to a range of other critical minerals such as cobalt, lithium, nickel, graphite and manganese to varying degrees, with some of these also carrying additional supply risks (cobalt’s specific jurisdictional risk being a case in point). And this is before evening getting into the added complication of China’s dominance of much of the EV supply chain and the implications of this for the EV transition in the context of geopolitical risk and resource nationalism.

Weighing up these mounting obstacles to achieving decarbonisation, it seems clear to me that the energy transition simply will not happen as policymakers expect or intend - it just isn’t possible geologically, financially, operationally or from a regulatory standpoint.

And so if one is open to the possibility that the energy transition will not happen as envisaged over the next ~10 years due to numerous supply-side constraints that cannot be resolved quickly, as an investor one must consider the question of what companies should do well in such a scenario?

Given the centrality of EVs to the energy transition, I think the auto sector is an interesting place to look, particularly when the world’s largest car manufacturer Toyota predicts that the transition to EVs will take longer than people expect. This view certainly seems reasonable in the context of the challenges highlighted above.

In turning over various rocks within this theme, I came across a very interesting Bloomberg Big Take podcast about a wave of catalytic converter thefts of in the US over 2021-2022. Catalytic converters contain platinum, palladium and rhodium, part of a group of precious metals collectively known as platinum group metals, or PGMs. As PGM prices spiked in 2020, the value of catalytic converters appreciated significantly, leading to a surge in thefts for their PGM components, which could be resold into the market at much higher prices (an accompanying article to the podcast which details the whole story can also be found here).

Interestingly, aside from their role in catalytic converters in ICE vehicles, PGMs also have a role to play in achieving net zero targets, and are regarded as critical minerals for the energy transition, given their use in decarbonisation technologies such as water electrolysers for green hydrogen production and fuel cells for vehicles and energy storage.

Having dug further into this corner of the precious metals market, I believe I have found a very interesting public equity situation that is mispriced as a “melting ice-cube” but in fact offers attractive exposure to the delayed EV transition theme, as well being a potential event-driven value situation.

This latest idea is a contrarian one, and the company is …